Under this rubric, I combine research concerned with the distribution of income and individual life chances. I am particularly interested in cumulative advantage, or “rich get richer” dynamics.

Taking a spatial perspective, I study agglomeration effects—the higher productivity, interconnectedness, and creativity in larger cities—and the urban-rural disparities they give rise to. This research draws attention to urban inequality and the increasingly uneven economic geography observed in many countries.

“Urban Scaling Laws Arise from Within-city Inequalities.” Nature Human Behaviour 7(3):365–374.

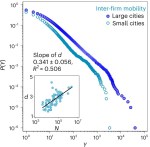

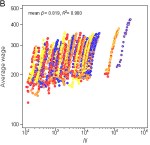

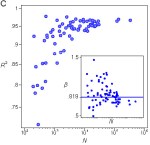

Urban scaling theory has accurately predicted city-level measures of urban outputs and the quality of life, but it has overlooked the stark inequalities that exist within cities. We demonstrate that urban scaling is largely a story of inequality, where the social and economic benefits of city growth mostly benefit urban elites. City tails are so important that any theory seeking to explain urban scaling—whether it be through interconnectivity, complexity, or other factors—must also explain the emergence of tail differences by city size. Covered in Nature Computational Science, Nature Cities, and El País.

“Urban Scaling and the Regional Divide.” Science Advances 5(1):eaav0042.

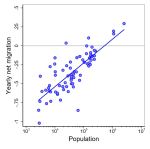

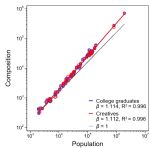

The higher than expected pace of life in large cities has been explained as an emergent consequence of increased social interactions in dense urban environments. Our research calls into question this influential theory of the self-reinforcing dynamics of city growth: Half of the previously reported “superlinear” scaling of cities is due to their differences in sociodemographic composition. Cities’ attraction of talent from their hinterlands amplifies these differences, adding to the cumulative decline of less populated regions. This paper also signifies that the existence of an aggregate pattern in social data says little about the causal processes that brought it about.

“Scaling Trajectories of Cities.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116(28):13759-61.

A particular perspective has come to dominate the science of cities, viewing cities of different sizes as scaled versions of one another, expected to go through similar stages of socioeconomic growth—only in different historical epochs. Swedish data show that dominant positions in the urban hierarchy advantage the largest cities—while smaller places are less resilient to economic shocks and social change. This advantage of prime cities places strong bounds on the self-similarity of urban growth.

“The Plateauing of Cognitive Ability among Top Earners.” European Sociological Review 39(5):820–833.

Those with the best-paying and most prestigious jobs wield the greatest economic and political power. But are these jobs really done by individuals of great intelligence? We connect intelligence tests taken of 59,000 Swedes to their wage. While the relationship is strong overall, it plateaus at high incomes: The bulk of citizens earn normal salaries that are clearly responsive to individual cognitive capabilities; but among top incomes, cognitive-ability levels do not differentiate wages. Hence, one cannot infer high intelligence from high income. Covered in Financial Times, L’Express, and WirtschaftsWoche.

See also our analysis of a much larger dataset of 750K Swedes.

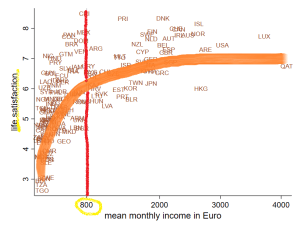

“Needs, Comparisons, and Adaptation: The Importance of Relative Income for Life Satisfaction.” European Sociological Review 29(1):86–104.

Three mechanisms are thought to govern the non-linear association of income and life satisfaction: the satisfaction of material needs, social comparison, and adaptation to life’s circumstances. We estimate the threshold for the fulfillment of basic material needs at approx. 800 Euros disposable income per month in Germany (GSOEP), in Munich (self-administered survey), and across 144 countries worldwide (World Database of Happiness). A new measurement method for social comparisons reveals that income comparisons are life-satisfaction-relevant for colleagues and average citizens, but not for friends and relatives. In sum, relative income (social as well as temporal) is more important for life satisfaction than absolute income.

Three mechanisms are thought to govern the non-linear association of income and life satisfaction: the satisfaction of material needs, social comparison, and adaptation to life’s circumstances. We estimate the threshold for the fulfillment of basic material needs at approx. 800 Euros disposable income per month in Germany (GSOEP), in Munich (self-administered survey), and across 144 countries worldwide (World Database of Happiness). A new measurement method for social comparisons reveals that income comparisons are life-satisfaction-relevant for colleagues and average citizens, but not for friends and relatives. In sum, relative income (social as well as temporal) is more important for life satisfaction than absolute income.