Social Norms

My research on social norms centers on how local conditions and strategies learned in daily interaction influence social behavior, and how they affect the tipping points for cooperation and normative change. I base this research on lab, online, field, and natural experiments. Bringing social context into controlled experiments is truly sociological as it acknowledges the importance of a multi-level explanation of individual action and collective outcomes.

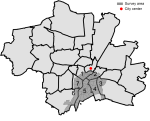

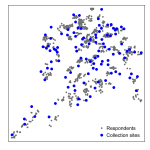

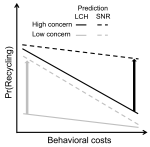

“Thou Shalt Recycle: How Social Norms of Environmental Protection Narrow the Scope of the Low-Cost Hypothesis.” Environment and Behavior 50(10):1059-91.

The “low-cost hypothesis” (LCH) asserts that attitudes explain behavior only if complying with personal convictions requires little effort. However, evidence for the LCH has remained contradictory. We combine a natural experiment exploiting households’ variation in geocoded walking distances to drop-off recycling sites in Munich, Germany (N=754) with an online survey (N=640) measuring local intensities of recycling norms. Our results suggest that normative change narrows the LCH’s scope to include only environmental action for which normative expectations are weak.

“Disorder, Social Capital, and Norm Violation: Three Field Experiments on the Broken Windows Thesis.” Rationality and Society 27(1):96-126.

Adding to the debate about the “broken windows” thesis, we explain minor norm violation by people’s beliefs on sanctioning probabilities conditional on contextual cues of local social control. In three field experiments, we show that minor norm violations foster further violations of the same and of different norms. Disorder effects are significantly stronger in neighborhoods with high social capital. Varying the net gains from deviance it shows that disorder effects are limited to low-cost situations. This paper received the Robert-K-Merton-Award in 2017 and the Anatol-Rapoport-Award in 2014.

Adding to the debate about the “broken windows” thesis, we explain minor norm violation by people’s beliefs on sanctioning probabilities conditional on contextual cues of local social control. In three field experiments, we show that minor norm violations foster further violations of the same and of different norms. Disorder effects are significantly stronger in neighborhoods with high social capital. Varying the net gains from deviance it shows that disorder effects are limited to low-cost situations. This paper received the Robert-K-Merton-Award in 2017 and the Anatol-Rapoport-Award in 2014.

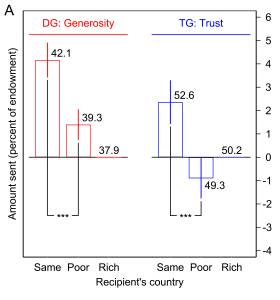

“Bounded Solidarity in Cross-National Encounters: Individuals Share More With Others From Poor Countries, But Trust Them Less.” Sociological Science 7:415-32.

Bringing together crowdworkers from 109 countries to take decisions on sharing and trusting, we show that cooperative behavior hinges on interaction partners’ identities. We cast information on identity by conveying interaction partners’ nationalities. In incentivized games of generosity and trust, we find clear evidence for in-group favoritism and—against this benchmark—demonstrate that individuals across the globe share more with but trust less in interaction partners from poor countries. Cultural distance moderates this status effect.

Bringing together crowdworkers from 109 countries to take decisions on sharing and trusting, we show that cooperative behavior hinges on interaction partners’ identities. We cast information on identity by conveying interaction partners’ nationalities. In incentivized games of generosity and trust, we find clear evidence for in-group favoritism and—against this benchmark—demonstrate that individuals across the globe share more with but trust less in interaction partners from poor countries. Cultural distance moderates this status effect.

“The Dark Side of Leadership: An Experiment on Religious Heterogeneity and Cooperation in India.” Journal of Socio-Economics 48(1):19-26.

Bringing Hindu and Muslim participants together in a lab experiment in India, we investigate voluntary contribution to public goods in a culturally heterogeneous context. While cultural heterogeneity does not affect contributions in the standard linear Public Goods Game, it reduces cooperation in the presence of a leader who makes their contribution before others do (‘leading by example’). Under cultural heterogeneity, poor leadership and uncertainty about followers’ reciprocity hinders the functionality of leadership as an institutional device to resolve social dilemmas.

Bringing Hindu and Muslim participants together in a lab experiment in India, we investigate voluntary contribution to public goods in a culturally heterogeneous context. While cultural heterogeneity does not affect contributions in the standard linear Public Goods Game, it reduces cooperation in the presence of a leader who makes their contribution before others do (‘leading by example’). Under cultural heterogeneity, poor leadership and uncertainty about followers’ reciprocity hinders the functionality of leadership as an institutional device to resolve social dilemmas.

Click here for a tutorial on how to analyze effects of cultural heterogeneity in lab experiments.

“On the Transportability of Laboratory Results.” Sociological Methods & Research 50(3): 1452-81.

We evaluate (1) sensitivity of laboratory results to locally recruited student-subject pools, (2) comparability of behavioral data collected online and in the laboratory, (3) generalizability of student-based results to the broader population, and (4), with a replication at Amazon Mechanical Turk, the stability of laboratory results across research contexts. Rates of behavior do not transport beyond specific implementations. This undermines the use of empirically motivated laboratory studies to establish descriptive parameters of human behavior. Treatment effects, by contrast, are remarkably robust to changes in samples and settings. Our results underscore lab and online experiments’ capacity to establish generalizable causal effects in theory-driven designs.

“Using Crowdsourced Online Experiments to Study Context-dependency of Behavior.” Social Science Research 59:68-82.

We use Mechanical Turk’s diverse participant pool to conduct online bargaining games in India and the US. By transporting a homogeneous decision situation into various living conditions, we explore context-dependency using variation in participants’ geographical location, regional affluence, and local social capital. We argue that quasi-experimental variation of the characteristics people bring to the experimental situation is the key potential of crowdsourced online designs.

We use Mechanical Turk’s diverse participant pool to conduct online bargaining games in India and the US. By transporting a homogeneous decision situation into various living conditions, we explore context-dependency using variation in participants’ geographical location, regional affluence, and local social capital. We argue that quasi-experimental variation of the characteristics people bring to the experimental situation is the key potential of crowdsourced online designs.

Click here for a tutorial on how to conduct large-scale online experiments on a crowdsourcing platform.

“The Use of Field Experiments to Study Mechanisms of Discrimination.” Analyse & Kritik 38(1):179-201.

This paper discusses social mechanisms of discrimination and reviews field experimental designs for their identification. We present common approaches to study discrimination based on observational data and laboratory experiments, discuss their strengths and weaknesses, and elaborate why unobtrusive field experiments are a promising complement. We highlight new field experimental designs that intervene in market activities—by varying costs and information for potential perpetrators—to identify causal pathways of discriminatio

This paper discusses social mechanisms of discrimination and reviews field experimental designs for their identification. We present common approaches to study discrimination based on observational data and laboratory experiments, discuss their strengths and weaknesses, and elaborate why unobtrusive field experiments are a promising complement. We highlight new field experimental designs that intervene in market activities—by varying costs and information for potential perpetrators—to identify causal pathways of discriminatio